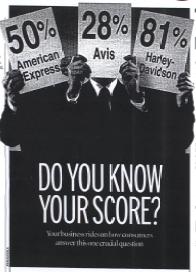

Some folks may have missed this due to the 4th of July holiday here in the States, but Matt Creamer over at Advertising Age wrote an article entitled "Do You Know Your Score?" [print edition, cover story and p. 24 for July 3rd, 2006].

Some folks may have missed this due to the 4th of July holiday here in the States, but Matt Creamer over at Advertising Age wrote an article entitled "Do You Know Your Score?" [print edition, cover story and p. 24 for July 3rd, 2006].

The article does a nice job of talking about how the use of the Net Promoter Score (NPS; the likelihood that a person will recommend an organization, brand, product or service [OBPS] to a friend or colleague) is becoming a standard across many different industries but especially among the word-of-mouth marketing community. The NPS score is calculated by subtracting the number of people who would not recommend the OBPS, or detractors, from the number of people who definitely would recommend the OBPS, or the promoters.

There are several advantages to using the NPS to track performance (whether it be product or service quality, customer service interactions, or the effectiveness of a word-of-mouth marketing campaign) including that it's easy to understand, it's straightforward to calculate, simple to administer, many companies are using it, and it has been tied to revenue growth (tested in both US and UK companies).

Fortunately the article also mentioned some of the drawbacks or cautions about using the score as the "only" or "ultimate" question. When I discuss the NPS during presentations I discuss its wonderful utility as well as four critiques:

1) Is revenue growth the only financial indicator that matters?First, besides revenue growth, other indicators are also important such as operating cash flow (the “lifeblood of the firm”), cash flow volatility (indicator of financial risk), Tobin’s Q (the relative value of such intangible assets as knowledge, human capital, brands, and relationships), and the price-to-book ratio (the ability to generate cash from assets). These other indicators are discussed in Neil Morgan and Lopo Rego’s letter-to-the-editor in the April 2004 Harvard Business Review (they are marketing professors at the business schools of UNC-Chapel Hill and University of Iowa, respectively). They conclude that revenue growth doesn’t necessarily equal success in these other metrics and thus companies shouldn't use NPS as the "only" thing to focus on in increasing shareholder value. They and others have also argued that customer satisfaction scores are also correlated with important indicators in certain industries.

2) Is the number of promoters, versus likelihood to promote, a better indicator of revenue growth?

3) Does NPS tell you what’s working and what’s not working?

4) How precise is NPS?

Second, Morgan and Rego argue that there is evidence that the number of people promoting may actually be a better indicator of revenue growth. However this is not consistently supported as Paul Marsden and colleagues, who have studied NPS among UK companies, did not found this in their research (learned via e-mail correspondence).

Third, an important concern is that NPS doesn't tell you what's working and what's not working. It's important to know why one has a high or low NPS so that an organization can make appropriate changes, or build on their strengths. Some people worry that organizations will stop at just measuring NPS and won't do enough follow-up research to understand why they're getting that score.

Finally, some people question how precise the NPS metric is. Pissed-off detractors who give an organization a "0" on the 0-to-10-point scale (0 - extremely unlikely to recommend, while 10 is extremely likely to recommend) are weighted the same as "passive" folks who give the organization a 5 or a 6 (this critique is discussed in a Business Week article). To be fair here, though, Fred does talk about how to address each of the three categories -- promoters, passives, and detractors -- differently when trying to improve one's performance and thus NPS score.

In their critique of the NPS in their HBR letter-to-the-editor, Morgan and Rego write that before an organization adopts the NPS, they should ask two questions:

1) What customer feedback measures best predict business performance in my industry?, and

2) What dimensions of my business performance am I trying to maximize?

According to them, an organization should only adopt the NPS if the answer to #1 is the number of net promoters, and to #2, revenue growth and nothing else. They also emphasize the importance of tracking what’s driving the recommendation as well as the number of customers making the WOM recommendations.

However, another way of thinking about whether a company should adopt the NPS is offered by Dr. Laura Brooks from Satmetrix. She argues in a blog post that a company should adopt the NPS if it actually motivates employees (and the organization as a whole) to change their behaviors.

And for a response to why some people hate the NPS, be sure to check out this blog post from Fred Reichheld.

Stay tuned for WOMMA's Measuring Word-of-Mouth, Volume 2 where we'll see how different WOMM companies are using the NPS in their businesses [disclosure: work group editor for this research book].

Other posts of interest:

My blog post about the London School of Economics study entitled "Advocacy Drives Growth"

My blog post about metrics used by WOM marketing companies to determine ROI

- Image above copyright by Advertising Age and Crain Communication. It is being used without their permission and knowledge but hopefully they won't mind.

-->

Tags: WOM word of mouth Word-of-Mouth Marketing buzz marketing viral marketing marketing communication